Second English Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in

In England, Parliament was struggling with the economic cost of the war, a poor 1646 harvest, and a recurrence of the plague. The moderate Presbyterian faction led by Denzil Holles dominated Parliament and was supported by the London

In England, Parliament was struggling with the economic cost of the war, a poor 1646 harvest, and a recurrence of the plague. The moderate Presbyterian faction led by Denzil Holles dominated Parliament and was supported by the London

In the north,

In the north,

House of Lords Journal Volume 10 19 May 1648: Letter from L. Fairfax, about the Disposal of the Forces, to suppress the Insurrections in Suffolk, Lancashire, and S. Wales; and for Belvoir Castle to be securedHouse of Lords Journal Volume 10 19 May 1648: Disposition of the Remainder of the Forces in England and Wales

(not mentioned in the Fairfax letter) {{authority control English Civil War Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1648 in England 1649 in England Conflicts in 1648 Conflicts in 1649

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

, which include the 1641–1653 Irish Confederate Wars

The Irish Confederate Wars, also called the Eleven Years' War (from ga, Cogadh na hAon-déag mBliana), took place in Ireland between 1641 and 1653. It was the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of civil wars in the kin ...

, the 1639-1640 Bishops' Wars, and the 1649–1653 Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland wi ...

.

Following his defeat in the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

, in May 1646 Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

surrendered to the Scots Covenanters

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

, rather than Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. By doing so, he hoped to exploit divisions between English and Scots Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, and English Independents. At this stage, all parties expected Charles to continue as king, which combined with their internal divisions, allowed him to refuse significant concessions. When the Presbyterian majority in Parliament failed to dissolve the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

in late 1647, many joined with the Scottish Engagers in an agreement to restore Charles to the English throne.

The Scottish invasion was supported by Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

risings in South Wales, Kent, Essex and Lancashire, along with sections of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. However, these were poorly co-ordinated and by the end of August 1648, they had been defeated by forces under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

and Sir Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

. This led to the Execution of Charles I

The execution of Charles I by beheading occurred on Tuesday, 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall. The execution was the culmination of political and military conflicts between the royalists and the parliamentarians in Eng ...

in January 1649 and establishment of the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

, after which the Covenanters crowned his son Charles II king of Scotland, leading to the 1650 to 1652 Anglo-Scottish War.

Background

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

ruled the three separate kingdoms of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in a personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

, which is why the conflicts that started in 1639 and lasted until 1651 are generally known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

. The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars began when Charles attempted to bring the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

or kirk into line with reforms recently enacted within the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. Known as Laudianism

Laudianism was an early seventeenth-century reform movement within the Church of England, promulgated by Archbishop William Laud and his supporters. It rejected the predestination upheld by the previously dominant Calvinism in favour of free will, ...

, these changes were opposed by English Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

and the vast majority of Scots, many of whom signed the National Covenant pledging to preserve the kirk by force of arms. Known as Covenanters

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

, their victory in the Bishops' Wars confirmed their control of Scotland and provided momentum for the king's opponents in England. The Covenanters passed laws that required all civil office-holders, MPs and clerics to sign the Covenant, and gave Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

the right to approve all Royal councillors in Scotland.

Tensions about religion and the governance of the nation were also rising in England. All parties agreed a 'well-ordered' monarchy was divinely mandated, but they disagreed on what 'well-ordered' meant, particularly with regards to the balance of power between king and Parliament, and on the question of where ultimate authority in clerical affairs lay. Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

generally supported a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

governed by bishops

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, appointed by, and answerable to, the king; Parliamentarians believed he ought to be answerable to the leaders of the church, who should be appointed by their congregations. The relationship between Charles and his English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

eventually broke down entirely, resulting in the outbreak of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

in 1642.

In England Charles's supporters, the Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

, were opposed by the combined forces of the Parliamentarians and the Scots. In 1643 the latter pair formed an alliance bound by the Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August 1 ...

, in which the English Parliament agreed to reform the English church along similar lines to the Scottish Kirk in return for the Scots' military assistance. After four years of war the Royalists were defeated and Charles surrendered to the Scots on 5 May 1646. The Scots agreed with the English Parliament on a peace settlement which would be put before the king. Known as the Newcastle Propositions, it would have required all the king's subjects in Scotland, England and Ireland to sign the Solemn League and Covenant, brought the church in each kingdom into accordance with the Covenant and with Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, and ceded much of Charles's secular authority as King of England to the English Parliament. The Scots spent some months trying to persuade Charles to agree to these terms, but he refused to do so. Under pressure from the English to withdraw their forces now the war was over, the Scots handed Charles over to the English Parliamentary forces in exchange for a financial settlement and left England on 3 February 1647.

In England, Parliament was struggling with the economic cost of the war, a poor 1646 harvest, and a recurrence of the plague. The moderate Presbyterian faction led by Denzil Holles dominated Parliament and was supported by the London

In England, Parliament was struggling with the economic cost of the war, a poor 1646 harvest, and a recurrence of the plague. The moderate Presbyterian faction led by Denzil Holles dominated Parliament and was supported by the London Trained Bands

Trained Bands were companies of part-time militia in England and Wales. Organised by county, they were supposed to drill on a regular basis, although this was rarely the case in practice. The regular army was formed from the Trained Bands in the ev ...

, the Army of the Western Association, leaders like Rowland Laugharne

Major General Rowland Laugharne (1607 – 1675) was a member of the Welsh gentry, and a prominent soldier during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, in which he fought on both sides.

Laugharne began his career as a page to Robert Devereux, 3rd ...

in Wales, and elements of the English navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fra ...

. By March 1647, the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

was owed more than £3 million in unpaid wages; Parliament ordered it to Ireland, stating only those who agreed to go would be paid. When their representatives demanded full payment for all in advance, it was ordered that it be disbanded, but its leaders refused to do so.

Charles now engaged in separate negotiations with different factions. Presbyterian English Parliamentarians and the Scots wanted him to accept a modified version of the Newcastle Propositions, but in June 1647, Cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a sopr ...

George Joyce

Cornet George Joyce (born 1618) was a low-ranking officer in the Parliamentary New Model Army during the English Civil War.

Between 2 and 5 June 1647, while the New Model Army was assembling for rendezvous at the behest of the recently formed ...

of the New Model Army seized Charles, and the army council pressed him to accept the Heads of Proposals

The Heads of Proposals was a set of propositions intended to be a basis for a constitutional settlement after King Charles I was defeated in the First English Civil War. The authorship of the Proposals has been the subject of scholarly debate, alt ...

, a less demanding set of terms which, crucially, did not require a Presbyterian reformation of the church. On 26 July pro-Presbyterian rioters burst into Parliament, demanding that Charles be invited to London; fearing that the king might be restored without concessions, the New Model Army took control of the city in early August, while the Army Council re-established their authority over the rank and file by suppressing the Corkbush Field mutiny

The Corkbush Field Mutiny (or Ware Mutiny) occurred on 15 November 1647, during the early stages of the Second English Civil War at the Corkbush Field rendezvous, when soldiers were ordered to sign a declaration of loyalty to Thomas Fairfax, the co ...

. The Eleven Members of Parliament whom the army identified as opposed to its interests were removed forcibly, and on August 20, Oliver Cromwell brought a regiment of cavalry to Hyde Park, rode with an escort to Parliament and pushed through the Null and Void Ordinance

The Null and Void Ordinance was an Ordinance passed by the Parliament of England on 20 August 1647. On 26 July 1647 demonstrators had invaded Parliament forcing Independent MPs and the Speaker to flee from Westminster. On 20 August, Oliver Cromw ...

, leading to the Presbyterian MPs withdrawing from Parliament. Charles eventually rejected the Heads of Proposals, and instead signed an offer known as the Engagement

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

, which had been thrashed out with the Scottish delegation, on 26 December 1647. Charles agreed to confirm the Solemn League and Covenant by Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

in both kingdoms, and to accept Presbyterianism in England, but only for a trial period of three years, in return for the Scots' assistance in regaining his throne in England.

When the delegation returned to Edinburgh with the Engagement, the Scots were bitterly divided on whether to ratify its terms. Its supporters, who became known as the Engagers, argued that it offered the best chance the Scots would get of acceptance of the Covenant across the three kingdoms, and that rejecting it risked pushing Charles to accept the Heads of Proposals. It was opposed by those who believed that to send an army into England on behalf of the king would be to break the Solemn League and Covenant, and that it offered no guarantee of a lasting Presbyterian church in England; the Kirk went so far as to issue a declaration on 5 May 1648 condemning the Engagement as a breach of God's law. After a protracted political struggle, the Engagers gained a majority in the Scottish Parliament, and it was accepted.

South Wales

Wales was a sensitive area, since most of it had been Royalist during the war, whileHarlech Castle

Harlech Castle ( cy, Castell Harlech; ) in Harlech, Gwynedd, Wales, is a Grade I listed medieval fortification built onto a rocky knoll close to the Irish Sea. It was built by Edward I during his invasion of Wales between 1282 and 1289 at t ...

was the last of their strongpoints to surrender in March 1647. The interception of secret messages between Charles and the Irish Confederacy

Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, was a period of Irish Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1649, during the Eleven Years' War. Formed by Catholic aristocrats, landed gentry, clergy and military ...

made it important to secure ports like Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

and Milford Haven

Milford Haven ( cy, Aberdaugleddau, meaning "mouth of the two Rivers Cleddau") is both a town and a community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, an estuary forming a natural harbour that has ...

, since they controlled shipping routes with Ireland. The Army Council viewed the local commanders, John Poyer

John Poyer (died 25 April 1649) was a Welsh soldier in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War in South Wales. He later turned against the parliamentary cause and was executed for treason.

Background

Poyer was a merchant and the m ...

and Rowland Laugharne

Major General Rowland Laugharne (1607 – 1675) was a member of the Welsh gentry, and a prominent soldier during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, in which he fought on both sides.

Laugharne began his career as a page to Robert Devereux, 3rd ...

, with suspicion, since they supported the Parliamentarian moderates. In July, Horton was sent to replace Laugharne, and secure these positions.

The revolt began in Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

, an area controlled by Parliament since early 1643. Like their New Model colleagues, the soldiers had not been paid for months, and feared being disbanded without their wages. In early March, Poyer, Governor of Pembroke Castle

Pembroke Castle ( cy, Castell Penfro) is a medieval castle in the centre of Pembroke, Pembrokeshire in Wales. The castle was the original family seat of the Earldom of Pembroke. A Grade I listed building since 1951, it underwent major restorati ...

, refused to relinquish command; he was soon joined by Rice Powell, who commanded Tenby Castle

Tenby Castle ( cy, Castell Dinbych-y-pysgod) was a fortification standing on a headland separated by an isthmus from the town of Tenby, Pembrokeshire, Wales. The remaining stone structure dates from the 13th century but there are mentions of the ...

, then by Laugharne. What began as a dispute over pay turned political when the Welsh rebels made contact with Charles. Most Royalists had sworn not to bear arms against Parliament and did not participate, one exception being Sir Nicholas Kemeys

Sir Nicholas Kemeys, 1st Baronet (before 1593 – 25 May 1648) was a Welsh landowner and soldier during the English Civil War in South Wales.

Lineage

The family claimed descent from a Stephen de Kemeys who held lands in the southern Welsh Ma ...

, who held Chepstow Castle

Chepstow Castle ( cy, Castell Cas-gwent) at Chepstow, Monmouthshire, Wales is the oldest surviving post-Roman stone fortification in Britain. Located above cliffs on the River Wye, construction began in 1067 under the instruction of the Norman L ...

for the king. By the end of April, Laugharne had assembled around 8,000 troops, and was marching on Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

, but was defeated at St Fagans on 8 May.

This ended the revolt as a serious threat, although Pembroke Castle did not surrender until 11 July, with a minor rising in North Wales

, area_land_km2 = 6,172

, postal_code_type = Postcode

, postal_code = LL, CH, SY

, image_map1 = Wales North Wales locator map.svg

, map_caption1 = Six principal areas of Wales common ...

suppressed at Y Dalar Hir in June and Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

retaken from the rebels in early October. The Welsh rising is generally not considered part of a planned, Royalist plot, but largely accidental; however, its retention was vital for future operations in Ireland.

Revolt against Parliament in Kent

A precursor toKent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

's Second Civil War had come on Wednesday, 22 December 1647, when Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

's town crier

A town crier, also called a bellman, is an officer of a royal court or public authority who makes public pronouncements as required.

Duties and functions

The town crier was used to make public announcements in the streets. Criers often dress ...

had proclaimed the county committee's order for the suppression of Christmas Day and its treatment as any other working day. However, a large crowd gathered on Christmas to demand a church service, decorate doorways with holly bushes, and keep the shops shut. This crowd – under the slogan "For God, King Charles, and Kent" – then descended into violence and riot, with a soldier being assaulted, the mayor's house attacked, and the city under the rioters' control for several weeks until forced to surrender in early January.

On 21 May 1648, Kent rose in revolt in the King's name, and a few days later a most serious blow to the Independents was struck by the defection of the Navy, from command of which they had removed Vice-Admiral William Batten

Sir William Batten (1601 to 5 October 1667) was an English naval officer and administrator from Somerset, who began his career as a merchant seaman, served as second-in-command of the Parliamentarian navy during the First English Civil War, th ...

, as being a Presbyterian. Though a former Lord High Admiral, the Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick is one of the most prestigious titles in the peerages of the United Kingdom. The title has been created four times in English history, and the name refers to Warwick Castle and the town of Warwick.

Overview

The first creation ...

, also a Presbyterian, was brought back to the service, it was not long before the Navy made a purely Royalist declaration and placed itself under the command of the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

. But Fairfax had a clearer view and a clearer purpose than the distracted Parliament. He moved quickly into Kent, and on the evening of 1 June, stormed Maidstone by open force, after which the local levies dispersed to their homes, and the more determined Royalists, after a futile attempt to induce the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

to declare for them, fled into Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

.

The Downs

Before leaving for Essex, Fairfax delegated command of the Parliamentarian forces to Colonel Nathaniel Rich to deal with the remnants of the Kentish revolt in the east of the county, where the naval vessels in the Downs had gone over to the Royalists and Royalist forces had taken control of the three previously Parliamentarian "castles of the Downs" (Walmer

Walmer is a town in the district of Dover, Kent, in England. Located on the coast, the parish of Walmer is south-east of Sandwich, Kent. Largely residential, its coastline and castle attract many visitors. It has a population of 6,693 (2001), i ...

, Deal

A deal, or deals may refer to:

Places United States

* Deal, New Jersey, a borough

* Deal, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* Deal Lake, New Jersey

Elsewhere

* Deal Island (Tasmania), Australia

* Deal, Kent, a town in England

* Deal, ...

, and Sandown

Sandown is a seaside resort and civil parishes in England, civil parish on the south-east coast of the Isle of Wight, United Kingdom with the resort of Shanklin to the south and the settlement of Lake, Isle of Wight, Lake in between. Together ...

) and were trying to take control of Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in Dover, Kent, England and is Grade I listed. It was founded in the 11th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history. Some sources say it is the ...

. Rich arrived at Dover on 5 June 1648 and prevented the attempt, before moving to the Downs. He took almost a month to retake Walmer (15 June to 12 July), before moving on to Deal and Sandown castles. Even then, due to the small size of Rich's force, he was unable to surround both Sandown and Deal at once and the two garrisons were able to send help to each other. At Deal he was also under bombardment from the Royalist warships, which had arrived on 15 July but been prevented from landing reinforcements. On the 16th, thirty Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

ships arrived with about 1500 mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

and – though the ships soon left when the Royalists ran out of money to pay them – this incited sufficient Kentish fear of foreign invasion to allow Sir Michael Livesey

Sir Michael Livesey, 1st Baronet (1614 - circa 1665), also spelt Livesay, was a Puritan activist and Member of Parliament who served in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. He was one of the regicides who approved the ...

to raise a large enough force to come to Colonel Rich's aid.

On 28 July, the Royalist warships returned and, after three weeks of failed attempts to land a relief force at Deal, on the night of 13 August managed to land 800 soldiers and sailors under cover of darkness. This force might have been able to surprise the besieging Parliamentarian force from the rear had it not been for a Royalist deserter who alerted the besiegers in time to defeat the Royalists, with less than a hundred of them managing to get back to the ships (though 300 managed to flee to Sandown Castle). Another attempt at landing soon afterwards also failed and, when on 23 August news was fired into Deal Castle on an arrow of Cromwell's victory at Preston, most Royalist hope was lost and two days later Deal's garrison surrendered, followed by Sandown on 5 September. This finally ended the Kentish rebellion. Rich was made Captain of Deal Castle, a position he held until 1653 and in which he spent around £500 on repairs.

Revolt elsewhere

InCornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It is ...

, North Wales

, area_land_km2 = 6,172

, postal_code_type = Postcode

, postal_code = LL, CH, SY

, image_map1 = Wales North Wales locator map.svg

, map_caption1 = Six principal areas of Wales common ...

, and Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

the revolt collapsed as easily as that in Kent. Only in South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

, Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

, and the north of England was there serious fighting. In the first of these districts, South Wales, Cromwell rapidly reduced all the fortresses except Pembroke. Here Laugharne, Poyer, and Powel held out with the desperate courage of deserters.

In the north,

In the north, Pontefract Castle

Pontefract (or Pomfret) Castle is a castle ruin in the town of Pontefract, in West Yorkshire, England. King Richard II is thought to have died there. It was the site of a series of famous sieges during the 17th-century English Civil War ...

was surprised by the Royalists, and shortly afterwards Scarborough Castle

Scarborough Castle is a former medieval Royal fortress situated on a rocky promontory overlooking the North Sea and Scarborough, North Yorkshire, England. The site of the castle, encompassing the Iron Age settlement, Roman signal station, an Ang ...

declared for the King as well. Fairfax, after his success at Maidstone and the pacification of Kent, turned northward to reduce Essex, where, under their ardent, experienced, and popular leader Sir Charles Lucas

Sir Charles Lucas, 1613 to 28 August 1648, was a professional soldier from Essex, who served as a Cavalier, Royalist cavalry leader during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Taken prisoner at the end of the First English Civil War in March 1646, ...

, the Royalists were in arms in great numbers. Fairfax soon drove Lucas into Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colches ...

, but the first attack on the town was repulsed and he had to settle down to a long and wearisome siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

.

A Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

rising is remembered for the death of the young and gallant Lord Francis Villiers, younger brother of George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, 20th Baron de Ros, (30 January 1628 – 16 April 1687) was an English statesman and poet.

Life

Early life

George was the son of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, favourite of James I a ...

, in a skirmish at Kingston (7 July 1648). The rising collapsed almost as soon as it had gathered force, and its leaders, the Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham held with Duke of Chandos, referring to Buckingham, is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been earls and marquesses of Buckingham.

...

and Henry Rich, the Earl of Holland

Earl of Holland was a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1624 for Henry Rich, 1st Baron Kensington. He was the younger son of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick, and had already been created Baron Kensington in 1623, also in the ...

, escaped, after another attempt to induce London to declare for them, to St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

and St Neots

St NeotsPronunciation of the town name: Most commonly, but variations that ''saint'' is said as in most English non-georeferencing speech, the ''t'' is by a small minority of the British pronounced and higher traces of in the final syllable ...

, where Holland was taken prisoner. Buckingham escaped overseas.

Lambert in the north

Major-GeneralJohn Lambert John Lambert may refer to:

*John Lambert (martyr) (died 1538), English Protestant martyred during the reign of Henry VIII

*John Lambert (general) (1619–1684), Parliamentary general in the English Civil War

* John Lambert of Creg Clare (''fl.'' c. ...

, a brilliant young Parliamentarian commander of twenty-nine, was more than equal to the situation. He left the sieges of Pontefract Castle

Pontefract (or Pomfret) Castle is a castle ruin in the town of Pontefract, in West Yorkshire, England. King Richard II is thought to have died there. It was the site of a series of famous sieges during the 17th-century English Civil War ...

and Scarborough Castle

Scarborough Castle is a former medieval Royal fortress situated on a rocky promontory overlooking the North Sea and Scarborough, North Yorkshire, England. The site of the castle, encompassing the Iron Age settlement, Roman signal station, an Ang ...

to Colonel Edward Rossiter, and hurried into Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

to deal with the English Royalists under Sir Marmaduke Langdale

Marmaduke Langdale, 1st Baron Langdale ( – 5 August 1661) was an English landowner and soldier who fought with the Royalists during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

An only child who inherited large estates, he served in the 1620 to 1622 Palati ...

. With his cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

, Lambert got into touch with the enemy about Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

and slowly fell back to Bowes

Bowes is a village in County Durham, England. Located in the Pennine hills, it is situated close to Barnard Castle. It is built around the medieval Bowes Castle.

Geography and administration Civic history

Bowes lies within the historic coun ...

and Barnard Castle

Barnard Castle (, ) is a market town on the north bank of the River Tees, in County Durham, Northern England. The town is named after and built around a medieval castle ruin. The town's Bowes Museum's has an 18th-century Silver Swan automato ...

. Lambert fought small rearguard actions to annoy the enemy and gain time. Langdale did not follow him into the mountains. Instead, he occupied himself in gathering recruits, supplies of material, and food for the advancing Scots.

Lambert, reinforced from the Midlands, reappeared early in June and drove Langdale back to Carlisle with his work half finished. About the same time, the local cavalry of Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

and Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

were put into the field for the Parliamentarians by Sir Arthur Hesilrige

Sir Arthur Haselrig, 2nd Baronet (1601 – 7 January 1661) was a leader of the Parliamentary opposition to Charles I and one of the Five Members whose attempted arrest sparked the 1642–1646 First English Civil War. He held various military an ...

, governor of Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

. On 30 June, under the direct command of Colonel Robert Lilburne

Robert Lilburne (1613–1665) was an English Parliamentarian soldier, the older brother of John Lilburne, the well known Leveller. Unlike his brother, who severed his relationship with Oliver Cromwell, Robert Lilburne remained in the army. He i ...

, these mounted forces won a considerable success at the River Coquet

The River Coquet runs through the county of Northumberland, England, discharging into the North Sea on the east coast at Amble. It rises in the Cheviot Hills on the border between England and Scotland, and follows a winding course across the l ...

.

This reverse, coupled with the existence of Langdale's Royalist force on the Cumberland side, practically compelled Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

to choose the west coast route for his advance. His Scottish Engager

The Engagers were a faction of the Scottish Covenanters, who made "The Engagement" with King Charles I in December 1647 while he was imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle by the English Parliamentarians after his defeat in the First Civil War.

Back ...

army began slowly to move down the long couloir

A ''couloir'' (, "passage" or "corridor") is a narrow gully with a steep gradient in a mountainous terrain.Whittow, John (1984). ''Dictionary of Physical Geography''. London: Penguin, p. 121. .

Geology

A couloir may be a seam, scar, or fissu ...

between the mountains and the sea. The Campaign of Preston which followed is one of the most brilliant in English history.

Campaign of Preston

On 8 July 1648, when the ScottishEngager

The Engagers were a faction of the Scottish Covenanters, who made "The Engagement" with King Charles I in December 1647 while he was imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle by the English Parliamentarians after his defeat in the First Civil War.

Back ...

army crossed the border

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders c ...

in support of the English Royalists,. the military situation was well defined. For the Parliamentarians, Cromwell besieged Pembroke in West Wales, Fairfax besieged Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colches ...

in Essex, and Colonel Rossiter besieged Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England, east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the towns in the City of Wake ...

and Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, su ...

in the north. On 11 July, Pembroke fell and Colchester followed on 28 August. Elsewhere the rebellion, which had been put down by rapidity of action rather than sheer weight of numbers, smouldered, and Charles, the Prince of Wales, with the fleet cruised along the Essex coast. Cromwell and Lambert, however, understood each other perfectly, while the Scottish commanders quarrelled with each other and with Langdale.

As the English uprisings were close to collapse, Royalist hopes centred on the Engager Scottish army . It was not the same veteran army of the Earl of Leven

Earl of Leven (pronounced "''Lee''-ven") is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1641 for Alexander Leslie. He was succeeded by his grandson Alexander, who was in turn followed by his daughters Margaret and Catherine (who are usu ...

, which had long been disbanded. For the most part it consisted of raw levies. The Kirk party

The Kirk Party were a radical Presbyterian faction of the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They came to the fore after the defeat of the Engagers faction in 1648 at the hands of Oliver Cromwell and the English Parlia ...

had refused to sanction the Engagement (an agreement between Charles I and the Scots Parliament for the Scots to intervene in England on behalf of Charles), causing David Leslie and thousands of experienced officers and men to decline to serve. The leadership of the Duke of Hamilton

Duke of Hamilton is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in April 1643. It is the senior dukedom in that peerage (except for the Dukedom of Rothesay held by the Sovereign's eldest son), and as such its holder is the premier peer of Sco ...

proved to be poor and his army was so ill provided for that as soon as England was invaded it began to plunder the countryside for sustenance.

On 8 July the Scots, with Langdale leading an advance guard, were near Carlisle, and reinforcements from Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

were expected daily. Lambert's cavalry were at Penrith, Hexham

Hexham ( ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Northumberland, England, on the south bank of the River Tyne, formed by the confluence of the North Tyne and the South Tyne at Warden, Northumberland, Warden nearby, and ...

and Newcastle, too weak to fight and having only skillful leading and rapidity of movement to enable them to gain time. Appleby Castle

Appleby Castle is in the town of Appleby-in-Westmorland overlooking the River Eden (). It consists of a 12th-century castle keep which is known as Caesar's Tower, and a mansion house. These, together with their associated buildings, are set ...

surrendered to the Scots on 31 July, whereat Lambert, who was still hanging on to the flank of the Scottish advance, fell back from Barnard Castle

Barnard Castle (, ) is a market town on the north bank of the River Tees, in County Durham, Northern England. The town is named after and built around a medieval castle ruin. The town's Bowes Museum's has an 18th-century Silver Swan automato ...

to Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

so as to close Wensleydale

Wensleydale is the dale or upper valley of the River Ure on the east side of the Pennines, one of the Yorkshire Dales in North Yorkshire, England.

It is one of only a few Yorkshire Dales not currently named after its principal river, but th ...

against any attempt of the invaders to march on Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wakefield in West Yorkshire, England, east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the towns in the City of Wake ...

. All the restless energy of Langdale's cavalry were unable to dislodge Lambert from the passes or to find out what was behind that impenetrable cavalry screen. The crisis was now at hand. Cromwell had received the surrender of Pembroke Castle on 11 July, and had marched off, with his men unpaid, ragged and shoeless, at full speed through the Midlands. Rains and storms delayed his march, but he knew that the Duke of Hamilton in the broken ground of Westmorland was still worse off. Shoes from Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

and stockings from Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its ...

met him at Nottingham

Nottingham ( , East Midlands English, locally ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east ...

, and gathering up the local levies as he went, he made for Doncaster

Doncaster (, ) is a city in South Yorkshire, England. Named after the River Don, it is the administrative centre of the larger City of Doncaster. It is the second largest settlement in South Yorkshire after Sheffield. Doncaster is situated in ...

, where he arrived on 8 August, having gained six days in advance of the time he had allowed himself for the march. He then called up artillery from Hull, exchanged his local levies for the regulars who were besieging Pontefract, and set off to meet Lambert. On 12 August he was at Wetherby

Wetherby () is a market town and civil parish in the City of Leeds district, West Yorkshire, England, close to West Yorkshire county's border with North Yorkshire, and lies approximately from Leeds City Centre, from York and from Harrogat ...

, Lambert at Otley

Otley is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish at a bridging point on the River Wharfe, in the City of Leeds metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. Historic counties of England, Historically a part of the West Ridi ...

, Langdale at Skipton

Skipton (also known as Skipton-in-Craven) is a market town and civil parish in the Craven district of North Yorkshire, England. Historically in the East Division of Staincliffe Wapentake in the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is on the River Air ...

and Gargrave

Gargrave is a large village and civil parish in the Craven district located along the A65, north-west of Skipton in North Yorkshire, England.

It is situated on the very edge of the Yorkshire Dales. The River Aire and the Leeds and Liverpool ...

, Hamilton at Lancaster, and Sir George Monro with the Scots from Ulster and the Carlisle Royalists (organized as a separate command owing to friction between Monro and the generals of the main army) at Hornby

Hornby may refer to:

Places In England

* Hornby, Lancashire

* Hornby, Hambleton, village in North Yorkshire

* Hornby, Richmondshire, village in North Yorkshire Elsewhere

* Hornby, Ontario, community in the town of Halton Hills, Ontario, Canad ...

. On 13 August, while Cromwell was marching to join Lambert at Otley, the Scottish leaders were still disputing whether they should make for Pontefract or continue through Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

so as to join Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

and the Cheshire Royalists.

Battle of Preston

On 14 August 1648 Cromwell and Lambert were at Skipton, on 15 August atGisburn

Gisburn (formerly Gisburne) is a village and civil parish within the Ribble Valley borough of Lancashire, England. Historically within the West Riding of Yorkshire, it lies northeast of Clitheroe and west of Skipton. The civil parish had a pop ...

, and on 16 August they marched down the valley of the Ribble towards Preston with full knowledge of the enemy's dispositions and full determination to attack him. They had with them troops from both the Army and the militias of Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, Durham, Northumberland and Lancashire, and were heavily outnumbered, having only 8,600 men against perhaps 20,000 of Hamilton's command. But the latter were scattered for convenience of supply along the road from Lancaster, through Preston, towards Wigan

Wigan ( ) is a large town in Greater Manchester, England, on the River Douglas, Lancashire, River Douglas. The town is midway between the two cities of Manchester, to the south-east, and Liverpool, to the south-west. Bolton lies to the nor ...

, Langdale's corps having thus become the left flank guard instead of the advanced guard.

Langdale called in his advanced parties, perhaps with a view to resuming the duties of advanced guard, on the night of 13 August, and collected them near Longridge

Longridge is a market town and civil parish in the borough of Ribble Valley in Lancashire, England. It is situated north-east of the city of Preston, at the western end of Longridge Fell, a long ridge above the River Ribble. Its nearest neigh ...

. It is not clear whether he reported Cromwell's advance, but, if he did, Hamilton ignored the report, for on 17 August Monro was half a day's march to the north, Langdale east of Preston, and the main army strung out on the Wigan road, Major-General William Baillie with a body of foot, the rear of the column, being still in Preston. Hamilton, yielding to the importunity of his lieutenant-general, James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar

James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar (s – March 1674), was a Scottish army officer who fought on the Royalist side in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

Early life

Livingston was the third son of Alexander Livingston, 1st Earl of Linlithgow an ...

, sent Baillie across the Ribble to follow the main body just as Langdale, with 3,000 infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

and 500 cavalry, met the first shock of Cromwell's attack on Preston Moor. Hamilton, like Charles at Edgehill, passively shared in, without directing, the Battle of Preston, and, though Langdale's men fought fiercely, they were driven to the Ribble after four hours' struggle.

Baillie attempted to cover the Ribble and Darwen

Darwen is a market town and civil parish in the Blackburn with Darwen borough in Lancashire, England. The residents of the town are known as "Darreners".

The A666 road passes through Darwen towards Blackburn to the north, Bolton to the sout ...

bridges on the Wigan road, but Cromwell had forced his way across both before nightfall. Pursuit was at once undertaken, and not relaxed until Hamilton had been driven through Wigan and Winwick to Uttoxeter

Uttoxeter ( , ) is a market town in the East Staffordshire district in the county of Staffordshire, England. It is near to the Derbyshire county border. It is situated from Burton upon Trent, from Stafford, from Stoke-on-Trent, from De ...

and Ashbourne. There, pressed furiously in rear by Cromwell's cavalry and held up in front by the militia of the midlands, the remnant of the Scottish army laid down its arms on 25 August. Various attempts were made to raise the Royalist standard in Wales and elsewhere, but Preston was the death-blow. On 28 August, starving and hopeless of relief, the Colchester Royalists surrendered to Lord Fairfax.

Execution of Charles I

The victors in the Second Civil War were not merciful to those who had brought war into the land again. On the evening of the surrender of Colchester, SirCharles Lucas

Sir Charles Lucas, 1613 to 28 August 1648, was a professional soldier from Essex, who served as a Cavalier, Royalist cavalry leader during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Taken prisoner at the end of the First English Civil War in March 1646, ...

and Sir George Lisle

Sir George Lisle (baptised 10 July 1615 – 28 August 1648) was a professional soldier from London who briefly served in the later stages of the Eighty and Thirty Years War, then fought for the Royalists during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Ca ...

were shot. Laugharne, Poyer and Powel were sentenced to death, but Poyer alone was executed on 25 April 1649, being the victim selected by lot. Of five prominent Royalist peers who had fallen into the hands of Parliament, three, the Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Holland, and Lord Capel, one of the Colchester prisoners, were beheaded at Westminster on 9 March. Above all, after long hesitations, even after renewal of negotiations, the Army and the Independents conducted "Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

Despite defeat in the ...

" of the House removing their ill-wishers, and created a court for the trial and sentence of King Charles I. At the end of the trial the 59 Commissioners (judges) found Charles I guilty of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, as a "tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy". He was beheaded on a scaffold in front of the Banqueting House

In English architecture, mainly from the Tudor period onwards, a banqueting house is a separate pavilion-like building reached through the gardens from the main residence, whose use is purely for entertaining, especially eating. Or it may be buil ...

of the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

on 30 January 1649. (After the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

in 1660, the regicides who were still alive and not living in exile were either executed or sentenced to life imprisonment.)

Capitulation of Pontefract Castle

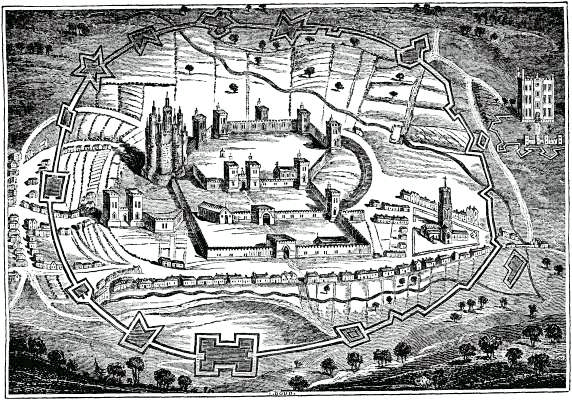

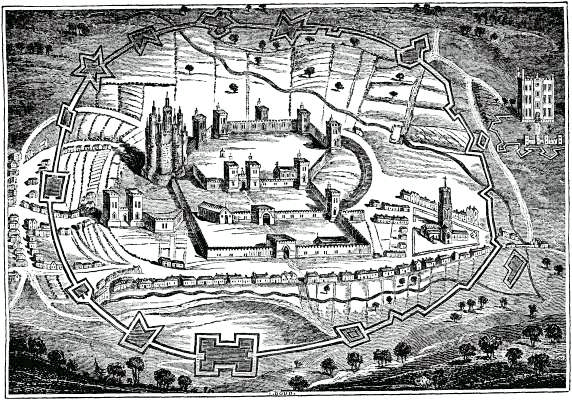

Pontefract Castle

Pontefract (or Pomfret) Castle is a castle ruin in the town of Pontefract, in West Yorkshire, England. King Richard II is thought to have died there. It was the site of a series of famous sieges during the 17th-century English Civil War ...

was noted by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

as " ..one of the strongest inland garrisons in the kingdom". Even in ruins, the castle held out in the north for the Royalists. Upon the execution of Charles I, the garrison recognised Charles II as King and refused to surrender. On 24 March 1649, almost two months after Charles was beheaded, the garrison of the last Royalist stronghold finally capitulated. Parliament had the remains of the castle demolished the same year.

Aftermath

Following Charles's execution, theCommonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

was established. In Scotland, Charles II became the new king, the resulting tensions leading to the Third English Civil War

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* H ...

in 1651.

See also

*Chronology of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Chronology of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms lists major events that occurred during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The presentation of the data in a table format allows interested parties to copy and transfer the data to other software or da ...

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;Attribution *Further reading

House of Lords Journal Volume 10 19 May 1648: Letter from L. Fairfax, about the Disposal of the Forces, to suppress the Insurrections in Suffolk, Lancashire, and S. Wales; and for Belvoir Castle to be secured

(not mentioned in the Fairfax letter) {{authority control English Civil War Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1648 in England 1649 in England Conflicts in 1648 Conflicts in 1649